Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Before Portsmouth: The Prehistoric Solent

Week 1 of 54: How Portsmouth was shaped? Discover how the prehistoric Solent river, Ice Age floods and rising seas shaped Portsea Island long before Portsmouth existed, with submerged forests and Mesolithic sites.

HISTORYPREHISTORICHOW PORTSMOUTH WAS SHAPED

Best of Portsmouth

12/1/20257 min read

Before there was a “Portsea Island,” before harbours and dockyards, there was a river. What is now the Solent began its life as River Solent, a mighty prehistoric waterway snaking across what is now southern England. The story of how the sea eventually swallowed that land and shaped the coastline that would cradle Portsmouth is a tale of climate change, geology, and slow-motion transformation over thousands of years.

From Chalk Valley to River Basin

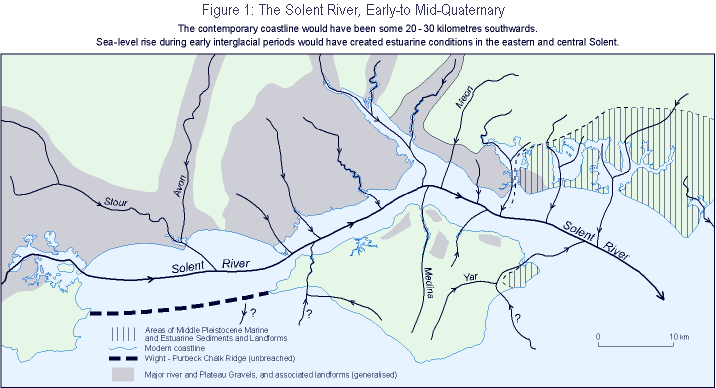

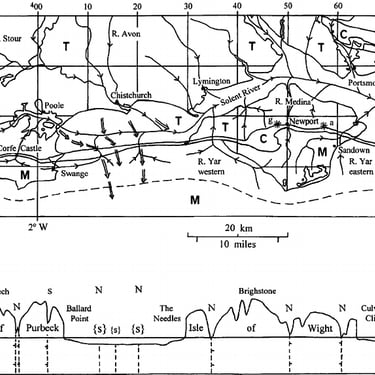

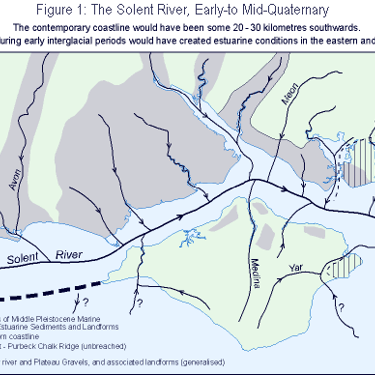

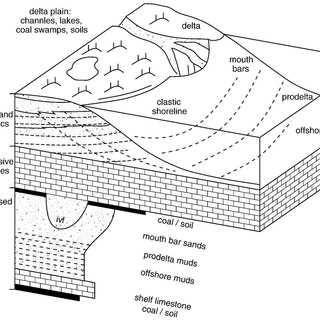

The bedrock beneath much of southern Hampshire (and the northern Isle of Wight) is chalk, part of a vast chalk formation that once ran unbroken from the Isle of Wight to the mainland. This resistant chalk ridge was the last land link between the island and the rest of Britain; remnants of it still stand today in the white cliffs of The Needles (off western Wight) and Old Harry Rocks (on the Dorset coast). Inland of that chalk spine lay much softer soils: sands, clays, and gravel deposits that were easily eroded by water. Through those weak materials ran a network of rivers, ancestors of today’s Test, Itchen, Avon, and others, all merging into a single greater river system. Over many thousands of years, these tributaries carved a deep valley through the region, creating a broad estuary that flowed west to east across the landscape. Geologists refer to this lost river as the Solent River, which in the Ice Age emptied eastward into a larger “Channel River” (a river that once ran along the floor of the dry English Channel) on its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

In short, the area of water that exists today, the strait between mainland Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, was once a sprawling river valley. It was a wooded valley teeming with wildlife, and eventually inhabited by people, long before it became a tidal gulf.

Ice Age, Climate Shifts & Sea-Level Change

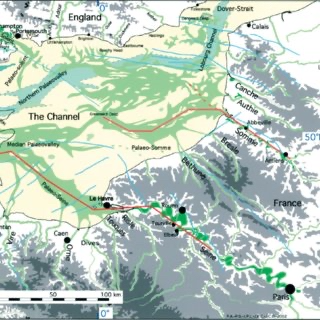

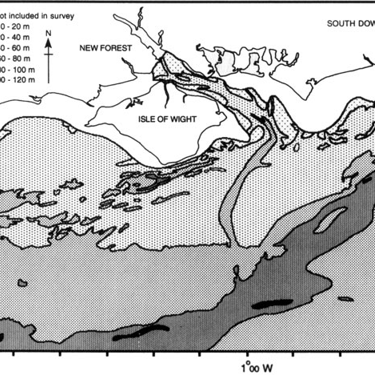

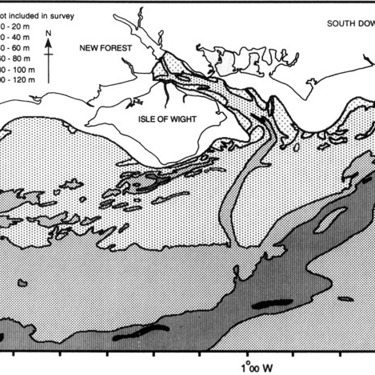

During the Pleistocene Ice Ages, with so much seawater locked up in glaciers, global sea levels dropped dramatically. At times, the ocean fell by as much as 120–140 meters, exposing vast tracts of seabed and turning coastal shelves into dry land. The British Isles were part of a contiguous European landmass then; one could walk from southern England to France because the entire English Channel area was above water. In this glacial world, the Solent River and its tributaries cut deeper into the landscape, since the rivers’ base level (the sea) was far lower than it is today. In fact, seismic surveys show the ancient Solent riverbed lies at least 45–50 meters below the present seabed in places, a measure of how deeply the river incised its valley when sea level was low.

Then, as the last Ice Age ended around 12,000 years ago, the climate warmed and glaciers melted. Meltwater flooded into rivers, swelling their flow, and global sea levels began to rise, inching back up the valleys. At the same time, the land itself was responding: the removal of heavy ice sheets in the north caused the northern parts of Britain to slowly rebound upward, while the south of England gradually sank downward, a see-saw effect known as isostatic adjustment. (This process is still ongoing, with southern England sinking a little more each century as the north continues to rise .) Over millennia, these forces combined to drown the great Solent Valley. The rising sea flooded the river’s mouth and then moved inland, turning riverbanks into estuaries and marsh. What had been freshwater valleys became tidal creeks and inlets. The once-continuous chalk ridge was finally breached by the encroaching sea around 7,500–8,000 years ago, disconnecting the Isle of Wight from the mainland. By about 6000 BC, the Solent took on its modern form: a tidal strait separating the island from Hampshire, with seawater flowing where mammoths and Mesolithic hunters once roamed.

That dramatic post-Ice Age sea rise, subtle on a human timescale but transformative over centuries, turned rivers into seas, valleys into bays, and plains into islands. The landscape of southern Britain was completely rearranged by water during the early Holocene.

Early Humans on the Old Shores

Even after the Ice Age, for a time, the Solent valley remained a habitable place for humans. As recently as 8,000 years ago (circa 6000 BC), sea levels were still lower than today, and the Solent was more like a marshy river valley than open sea. Along its banks lived Mesolithic people. One extraordinary glimpse of their presence comes from Bouldnor Cliff, an underwater archaeological site off the Isle of Wight. Here, at about 11 meters below today’s sea level, divers have found the submerged remains of an 8,000-year-old settlement. The discoveries are striking: wooden platforms and stakes driven into the earth, large mounds of worked flint and burnt stones, layers of charcoal and hardened clay (remnants of ancient hearths or floors), and even a carved wooden artefact that may be part of a log boat. These artefacts suggest Mesolithic inhabitants were building structures, lighting fires, woodworking, and perhaps even boat-building on the Solent’s shores long before they were inundated.

The flooding of the valley ended that chapter of human habitation, but it also preserved a remarkable record of it. As the sea slowly advanced, it buried ancient campsites and forests under layers of mud, silt, and peat, creating waterlogged conditions in which organic materials that normally decay (like wood, plants, and bone) survived in situ. At Bouldnor Cliff, for example, the rising waters sealed a prehistoric woodland and occupation surface under sediments, protecting fragile items. Thanks to this, archaeologists have recovered wooden tools and structural timbers, intact hearths with charcoal and hazelnut shells, and even traces of wheat DNA preserved in submerged soils. Such finds offer an unparalleled window into prehistoric Britain’s environment and human activities. Likewise, along the Hampshire coast, divers and fishermen have encountered the stumps of long-drowned trees and peat beds on the seafloor, ghostly reminders of the old forests that once covered the landscape.

It’s also worth noting that the Solent region’s deep history of human presence goes back much further. In geological terms, the area’s terrace gravels, ancient riverbank sediments now found at various elevations on land, have yielded stone tools from the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic era (hundreds of thousands of years ago). In other words, very early humans (like Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals) left artefacts in what was the Solent River system long before it became the coast of England. So, well before any stone castles or naval dockyards, long before a town called Portsmouth existed, people lived, hunted, and travelled in this landscape… and then the waters came to reshape it.

From Valleys to Islands. How Portsea Emerged!

As the post-Ice Age seas rose, low-lying parts of the Hampshire coastal plain gradually filled with water. The broad Solent valley became a wide tidal channel, and side valleys and river basins were also inundated to form estuaries. High ground, however, stayed above water as the seas encroached, effectively turning hilltops into islands. This is how Portsea Island, the piece of land on which modern Portsmouth sits, was born. It wasn’t formed by volcanic uplift or anything sudden; it was simply a higher section of land that remained dry while the surrounding lower terrain flooded. Over time (by the Bronze Age, a few thousand years ago), Portsea’s surrounding marshes and channels had opened into continuous water, isolating that patch of land completely. In a sense, Portsea “emerged” as an island not by rising, but by everything around it sinking into the sea.

The same pattern repeated all along the Solent shores. The drowned river valleys became the Solent’s many harbours and inlets. For example, the valley on the west side of Portsea Island filled to become Portsmouth Harbour, while the one on the east became Langstone Harbour. What had been stream courses or hollows turned into tidal creeks and mudflats. The newly formed Solent Strait, shielded by the Isle of Wight, featured calmer, sheltered waters that made for excellent natural anchorages. This was geological luck that centuries later proved crucial: those flooded, sheltered harbours set the stage for Portsmouth’s development as a naval and maritime hub. By creating a complex coastline of deep-water channels and protective bays, nature had built an ideal haven for ships. (Of course, these waterways are relatively shallow and interwoven, which imposed size limits and navigation challenges for ships – but they also offered protection and multiple safe moorings.) In short, the same slow changes that turned Portsmouth’s area from dry land to an archipelago also gifted it the geography that British seafarers would leverage millennia afterwards.

Thus, the landscape beneath modern Portsea Island, a mix of chalk highlands, river-terrace gravels, and flooded lowlands, is a direct legacy of Ice Age climate swings and sea-level rise. Portsmouth exists where it does because of those ancient transformations.

Why This Ancient History Matters

Shallow, complex waters: Understanding that Portsmouth’s harbours were once dry land helps explain their quirks today. The Solent and its estuaries are relatively shallow, drowned landscapes with sandbanks and winding channels, rather than very deep, scoured fjords. The legacy of the old river valleys makes local tidal patterns and navigation tricky; the Solent even has an unusual double high-tide that mariners must account for. Many a sailor has noted the Solent’s strong currents and quickly changing sea states, rooted in its post-glacial geography. Knowing the origin of these features is useful for anyone who sails or manages these waters.

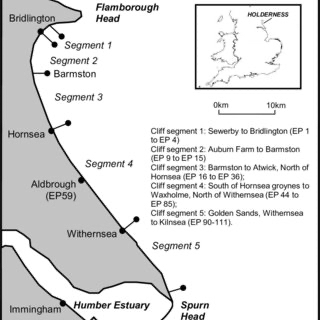

Coastlines can change dramatically: The submerged forests and Stone Age sites under the Solent are a vivid reminder that sea levels have risen significantly and are still rising. Within a few millennia, an inhabited river valley became a wide strait. Seeing how the coastline shifted since 8000 years agts modern sea-level rise in perspective. It happened slowly by human standards, but it happened. And it’s ongoing: the land around Portsmouth is still sinking subtly, and the sea is still creeping higher. The ancient floods that created the Solent foreshadow the kind of gradual coastal changes that our descendants might witness in the future.

A deeper sense of place: For a local history lover (like the writer of this series), this deep-time perspective adds rich context to Portsmouth’s story. It’s fascinating (and humbling) to realise that the bustling modern city grew out of a drowned prehistoric landscape. The streets of Portsmouth are laid atop what was once riverbank soil and forest floor. Appreciating that continuity from ancient nature to contemporary urban life can inspire a more profound connection to the place. It reminds us that Portsmouth’s history doesn’t begin with written records or medieval foundations, but with the very earth and sea that set the stage. In the ebb and flow of tides and the contours of the coastline, the ancient past is still with us.

Gallery

What's in the Photos

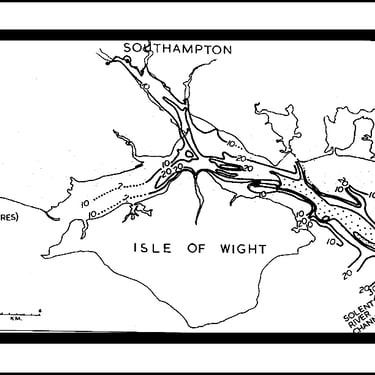

“Palaeogeography of the Solent River” — this reconstructs the ancient river-valley drainage system before the sea flooded in, showing the path of the now-extinct River Solent and its tributaries.

“Buried valley of the Solent estuarine system” — shows the subsurface valley structure (gravel bases etc.) that underlie the modern seabed under what is now the Solent and Southampton Water.

“Bedrock surface contours map” — reveals underlying chalk-bedrock geometry and how the present-day sea masks what was once dry land.

Modern map (Solent/Isle of Wight + Portsmouth/Portsea Island) — serves as the “Now” half: the coastlines, harbour, island, and straits as people know them today.

Overlay / comparative map (ancient river valley vs modern coastline) — best for visualising how much geography has changed: where land was, where water is now.

Low sea-level Ice Age map (southern England) — helps set context: how the sea-level drop exposed continental shelf, allowing the river system to carve channels.